The provision of care coordination services has increased in recent years as payors have begun reimbursing these types of services, through a combination of fee-for-service, bundled payments, and value-based care models. This fourth installment in a five-part series on the valuation of care coordination services reviews the reimbursement environment in which care coordination services are provided.

The U.S. government is the largest payor of medical costs, through Medicare and Medicaid, and has a strong influence on physician reimbursement. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has been a primary driver in establishing standardized reimbursement for care coordination, largely through specific Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) and Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) codes in the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (MPFS). As is common with reimbursement of other healthcare services, the prevalence of Medicare and Medicaid in the healthcare marketplace often results in their acting as a price and policy setter and being used as a benchmark for private reimbursement rates.

Medicare pays for physician services through its MPFS, which calculates payments according to Medicare’s Resource Based Relative Value Scales (RBRVS) system, which assigns relative value units (RVUs) to individual procedures based on the resources required to perform each procedure. Under this system, each procedure in the MPFS is assigned RVUs for three categories of resources:

Physician work (wRVUs), which represents the physician’s contribution of time and effort to the completion of a procedure. The higher the value of the code, the more skill, time, and work it takes to complete.

Practice expense (PE RVUs), which is based on direct and indirect physician practice expenses involved in providing healthcare services. Direct expense categories include clinical labor, medical supplies, and medical equipment. Indirect expenses include administrative labor, office expenses, and all other expenses.

Malpractice expense (MP RVUs), which corresponds to the relative malpractice practice expenses for medical procedures. These values are updated at least every five years and typically comprise the smallest component of the RVU.

1

Each procedure’s RVUs are adjusted for local geographic differences using Geographic Practice Cost Indexes (GPCIs) for each RVU component. Once the procedure’s RVUs have been modified for geographic variance, they are summed, and the total is then multiplied by a conversion factor (CF) to obtain the dollar amount of governmental reimbursement.

The formula for calculating the Medicare physician reimbursement amount for a specific procedure and location is as follows:2

Payment = [(wRVU x GPCI work) + (RVU PE x GPCI PE) + (RVU MP × GPCI MP)] × CF

The GPCI accounts for the geographic differences in the costs of maintaining a practice. Every Medicare payment locality has a GPCI for the work, practice, and malpractice component.3 A locality’s GPCI is determined by taking into consideration median hourly earnings of workers in the area, office rents, medical equipment and supplies, and other miscellaneous expenses.4 There are currently 109 GPCI payment localities.5

The CF is a fixed monetary amount that is multiplied by the RVU from a locality to determine the payment amount for a given service.6 The CF is updated annually according to the predetermined update schedule set forth in the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA); while this update has been 0% from 2020 through 2025, it will increase to 0.25% starting in 2026.7 MACRA also includes several provisions related to financial rewards for providers who furnish efficient, high quality healthcare services.8

For 2025, payment amounts were cut for the fifth straight year, with the MPFS conversion factor decreasing by 2.93%.9 However, CMS recently finalized an increase of over 3.25% to the MPFS for 202610

The MPFS pays for several care coordination (also called care management) activities. These can largely be categorized into five types of care coordination:

Chronic care management (CCM), which includes monthly management of “a patient’s multiple (2 or more) chronic conditions.”

11 Such chronic conditions include:

Alzheimer’s disease and related dementia;

Arthritis

(osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis);

Asthma;

Atrial fibrillation;

Autism spectrum disorders;

Cancer;

Cardiovascular disease;

Chronic obstructive pulmonary

disease (COPD);

Depression;

Diabetes;

Glaucoma;

HIV and AIDS;

Hypertension (high blood pressure); and,

Substance use disorders.

12

Transitional care management (TCM), which “begins when a physician discharges a Medicare patient from an inpatient stay and helps “patients transition back to a community setting after a stay at certain facility types.”

13

Remote patient monitoring (RPM) allows providers to monitor and manage patients’ acute and chronic conditions on an ongoing basis outside of the traditional clinical setting through the use of digital technologies.

14

Principal care management (PCM), which was added in 2020, focuses “on a single, high-risk chronic condition expected to last at least 3 months that places the patient at significant risk of hospitalization, acute exacerbation or decompensation, functional decline, or death.”

15

Advanced Primary Care Management (APCM), which was added in 2025, “includes the essential elements of advanced primary care,” including PCM, TCM, and CCM, but may only be billed by primary care providers.

16 Unlike other care coordination codes, APCM codes are not time-based, so as to reduce the administrative burden.

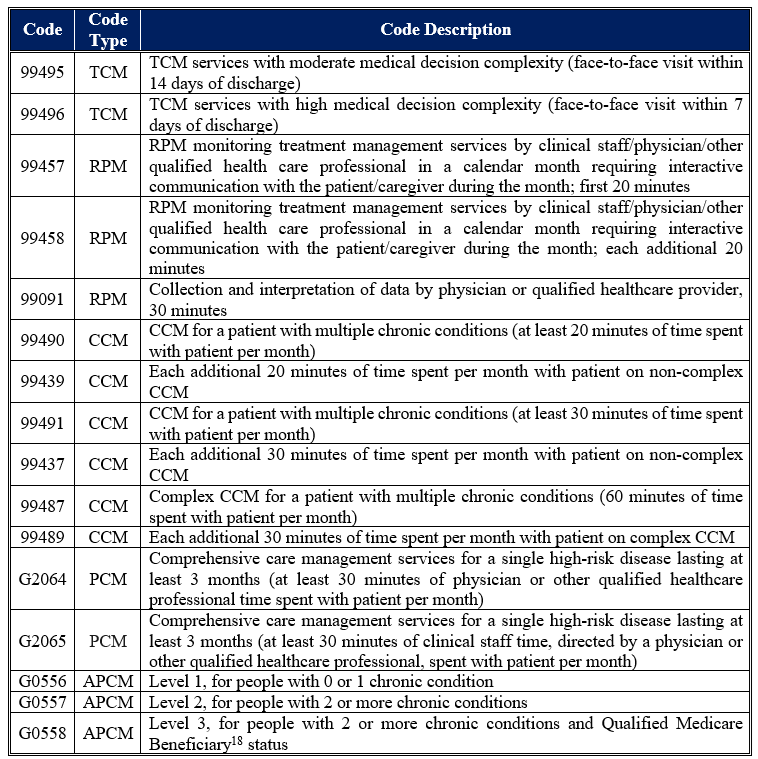

a non-exhaustive list of care coordination activities reimbursed by Medicare (and their corresponding CPT codes) is set forth below in Table 1.

Importantly, despite the above-listed care coordination activities for which providers may be reimbursed, the specific tasks involved in the primary-to-specialty care referral that commences the coordination of specialty care (e.g., identifying an appropriate specialist; gathering pertinent information from insurance carriers or other staff to determine financial responsibility; obtaining referral authorization from insurance carriers and relaying such authorizations or denials to the patient and the provider; resolving pre-authorization, registration, or other referral-related issues prior to a patient’s appointment) is not reimbursed by Medicare (or other payors).19 Research indicates that care coordination activities not only achieve the goals of coordinated patient care, but also results in increased revenue for providers.20 This implies that the increasing coverage of, and reimbursement for, care coordination activities are achieving payors’ goals. This raises the question of whether reimbursement for care coordination may further expand in the near future.

The final installment in this five-part series will explore the regulatory environment in which care coordination services are provided.

“Understand how Medicare payments are made by learning how to calculate them” By G.J. Verhovshek, MA, CPC, AAPC, November 1, 2011, https://www.aapc.com/blog/23479-demystify-the-physician-fee-schedule/#:~:text=RVU%20Totals%20Are%20the%20Sum,least%20once%20every%20five%20years. (Accessed 9/4/25).

“Medicare Program; Payment Policies Under the Physician Fee Schedule and Other Revisions to Part B for CY 2016; Final Rule” Federal Register Vol. 80, No. 220 (November 16, 2015), p. 70890.

“Documentation and Files: NATIONAL PHYSICIAN FEE SCHEDULE AND RELATIVE VALUE FILES” Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, January 8, 2025, https://www.cms.gov/medicare/physician-fee-schedule/search/documentation (Accessed 2/10/25).

“Physician Reimbursement Under Medicare” By Alan M. Scarrow, MD, Neurosurgical Focus, Vol. 12, No. 4 (April 2002), p. 2.

“Medicare PFS Locality Configuration” Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, September 10, 2024, https://www.cms.gov/medicare/payment/fee-schedules/physician/locality-configuration (Accessed 2/10/25).

“Physician and Other Health Professional Payment System” Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, Payment Basics, October 2024, https://www.medpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/MedPAC_Payment_Basics_24_Physician_FINAL_SEC.pdf (Accessed 7/17/25).

“Chapter 1: Reforming physician fee schedule updates and improving the accuracy of relative payment rates” in “Report to the Congress: Medicare and the Health Care Delivery System” Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, June 2025, available at: https://www.medpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Jun25_Ch1_MedPAC_Report_To_Congress_SEC.pdf (Accessed 7/17/25), p. 13.

“Calendar Year (CY) 2025 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule Final Rule” Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, November 1, 2024, https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/calendar-year-cy-2025-medicare-physician-fee-schedule-final-rule (Accessed 9/4/25).

For more information, see the Health Capital Topics article in this issue titled “2026 MPFS Finalized.”

“Chronic Care Management Services” Medicare Learning Network, MLN909188, June 2025, available at: https://www.cms.gov/files/document/chroniccaremanagement.pdf (Accessed 11/12/25), p. 3.

“Transitional Care Management Services” Medicare Learning Network, MLN908628, August 2025, available at: https://www.cms.gov/files/document/mln908628-transitional-care-management-services.pdf (Accessed 11/12/25), p. 3.

Also called remote physiologic monitoring (RPM). “Remote Patient Monitoring” Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, May 5, 2025, https://www.cms.gov/medicare/coverage/telehealth/remote-patient-monitoring#:~:text=Remote%20patient%20monitoring%20allows%20a,to%20make%20informed%20treatment%20decisions. (Accessed 11/12/25).

“Chronic Care Management Services” Medicare Learning Network, MLN909188, June 2025, available at: https://www.cms.gov/files/document/chroniccaremanagement.pdf (Accessed 11/12/25), p. 11; “CY 2020 PHYSICIAN FEE SCHEDULE FINAL RULE SUMMARY” National Association of Epilepsy Centers, available at: https://naec-epilepsy.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/NAEC-2020-MPFS-Summary-and-Charts-FINAL.pdf (Accessed 11/12/25), p. 3.

Medicare Learning Network, MLN908628, August 2025; Medicare Learning Network, ICN MLN909188, July 2019; “Principal Care Management Services” American Society of Clinical Oncology, available at: https://practice.asco.org/sites/default/files/drupalfiles/2020-02/PCM2020.pdf (Accessed 10/12/21).

A Qualified Medicare Beneficiary (QMB) is a low-income Medicare beneficiary who also qualifies for assistance from their state’s Medicaid program to cover most out-of-pocket Medicare costs. “What Is the Qualified Medicare Beneficiary (QMB) Program?” By Jill Seladi-Schulman, PhD., Healthline, April 25, 2025, https://www.healthline.com/health/medicare/qmb-medicare-savings-program (Accessed 11/12/25).

“Mastering care coordination” By Rachel Zimlich, RN, Medical Economics Journal, Vol. 97, Issue 9 (May 2020), https://www.medicaleconomics.com/view/mastering-care-coordination (Accessed 11/12/25).

See, e.g., “Practices That Adopted Remote Physiologic Monitoring Increased Medicare Revenue And Outpatient Visits” By Mitchell Tang, et al., Health Affairs (November 2025), https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/full/10.1377/hlthaff.2025.00683 (Accessed 11/12/25).