The demand for care coordination services is likely to increase in the near future, due to the shift in the U.S. healthcare delivery system from volume-based to value-based reimbursement, the aging Baby Boomer population, and the increasing prevalence of chronic diseases. At the same time, the supply of primary care providers is insufficient to meet current demand, much less this greater future demand. This second installment in a five-part series on the valuation of care coordination services reviews the demand for, and supply of, care coordination services.

Demand for Care Coordination Services

As noted in the first installment in this series, the U.S. healthcare delivery system is shifting from volume-based to value-based reimbursement, which requires providers to work together to reduce cost and increase quality, drives demand for care coordination services. In fact, care coordination to prevent fragmentation is a sine qua non of value-based payment models such as accountable care organizations (ACOs).1 Some of the “low hanging fruit” for providers seeking to streamline costs and improve quality may be focusing on providing higher-quality, cost-effective care to elderly patients and patients with one or more chronic diseases. For example, a 2015 study found that inadequate care coordination may increase the average costs of chronic disease management by over $4,500 over three years with no improvements in the quality of care.2 More and more value-based reimbursement models are requiring care coordination in order to achieve financial rewards (e.g., by avoiding underpayments due to more readmissions and higher costs due to preventable system utilization), especially for episode-based payments.3 Consequently, care coordination services have emerged as a critical infrastructure component, bridging the gaps between primary care providers, specialists, hospitals, post-acute care facilities, and community-based organizations. Healthcare providers increasingly rely on dedicated care coordinators, nurse navigators, and interdisciplinary care teams to manage complex patient populations, reduce readmissions, improve medication adherence, and ensure seamless transitions across care settings.

In addition to the shift to value-based care, the demand for care coordination services – driven by the demand for healthcare services generally – is expected to rise with the aging American population, particularly the Baby Boomer cohort.4 By 2030, 20% of the U.S. population will be age 65 and older.5 The growing elderly patient population utilizes a greater proportion of (and expenditures related to) medical services relative to the rest of the general population,6 and as such may comprise an outsized portion of the patient population in future years. Notably, older adults are also more likely to suffer from chronic diseases.7

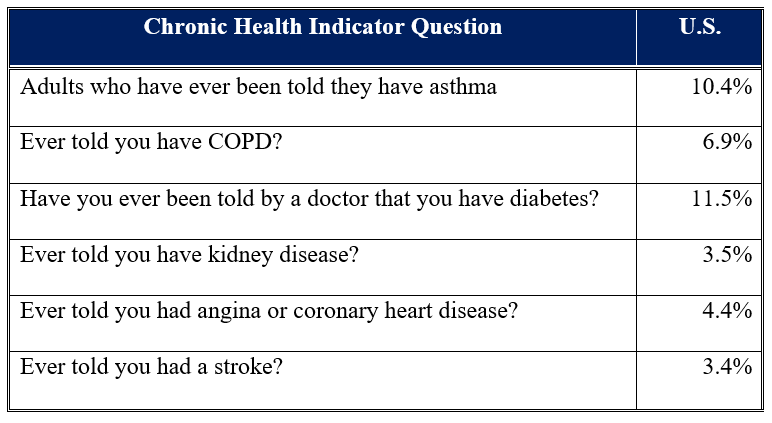

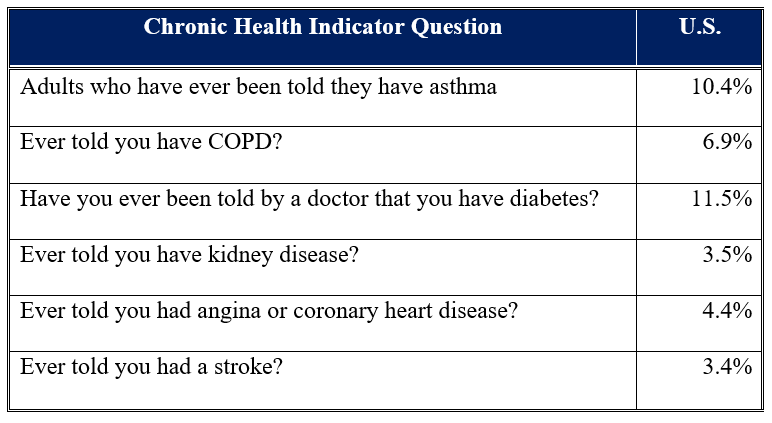

Demand for care coordination services is also likely to increase in the near future due to the increasing prevalence of chronic diseases, which are the leading cause of illness, disability, and death in the U.S.8 The prevalence of chronic disease (e.g., heart disease, cancer, diabetes, obesity, hypertension) nationwide has been on the rise, with approximately 129 million Americans suffering from at least one chronic disease, 42% having two or more chronic diseases, and 12% having five or more.9 Among older adults, approximately 95% have at least one chronic disease, and nearly 80% have at least two.10 The prevalence of these various chronic diseases are set forth below in Table 1.

Table 1: Percent of U.S. Population with Various Chronic Health Diseases11

Notably, the most frequent diagnoses for hospitalizations include heart failure and diabetes, two chronic diseases.12

The prevalence of chronic diseases may be higher in rural areas, where residents are generally less healthy than those in urban areas; they also face healthcare access issues (particularly to primary care), as rural areas have more acute physician shortages, and rural hospitals typically operate on much thinner operating margins, hindering the breadth of services offered.13 This has manifested in a substantial increase in patient visits to rural emergency departments.14

Four common behaviors responsible for the majority of illness, disability, and premature death related to chronic diseases include: smoking; excessive alcohol use; poor nutrition; and poor physical activity.15 As such, despite the fact that chronic diseases are among the most common and costly health problems in the U.S., they are also the most preventable.

Not only will demand for care coordination services likely increase in the future, but demand does not seem to be met by the current supply of care coordination services. A 2022 study found that “[a]pproximately 42% of older adults perceived poor care coordination” and only 33% had ever met with a formal care coordinator.16 A 2016 CareMore Health and Harris Poll found that 70% of elderly patients managing a chronic illness reported needing stronger care coordination from their clinicians.17

Supply of Care Coordination Services

As alluded to in this series, all of a patient’s providers are required to have effective team care coordination. First and foremost, it is important that the care coordination team have a “quarterback.”18 The quarterback is typically responsible for: “Overseeing care; coordinating diagnoses, tests, and treatments; advocating for patients; identifying and respecting patient values; proactively communicating; and solving problems.”19 While this role is often assigned to the primary care provider (PCP), some industry stakeholders argue that PCPs should not be the process’s point person because many physicians simply do not have the time to address care coordination.20 While physicians are necessary for the patient diagnosis and the development of a treatment plan, the remaining tasks can be taken on by others.21 Therefore, the supply of care coordination services (the need of which is triggered by the referral of a patient by a PCP to another physician) may be determined in part by: (1) the number of PCPs, and (2) the time that PCPs are able to devote to care coordination services.

By 2028, approximately 40% of the U.S. physician workforce will be over the age of 65.22 Compared to physicians under the age of 40:

Physicians aged 60-64 work 1.7 fewer hours per week;

Physicians aged 65-69 work 5.5 fewer hours per week; and,

Physicians over the age of 70 work 11.4 fewer hours per week.

23

Combined with the strong growth in demand from the number of Americans over the age of 65, this indicates that the U.S. may soon face a serious shortage of PCPs. In addition to retiring physicians and fewer number of overall hours worked by physicians approaching retirement, the impending internist workforce shortage may be further exacerbated by the lower number of medical students who are choosing to specialize in primary care over other specialties (primarily because of wage considerations).24 In fact, less than 25% of all physicians practice in a primary care specialty, less than half of the ideal ratio of 50%.25 Further, fewer physicians are choosing to specialize in family medicine and obstetrics and gynecology, while the number of internists and pediatricians continues to rise.26 Nevertheless, by 2034, the shortfall of PCPs is estimated be somewhere between 17,800 and 48,000 full-time equivalents (FTEs).27

In 2023, there were 33 family/general practice physicians per 100,000 population in the U.S.,28 which equates to approximately 2,360 adults per PCP. This estimate is in line with the 2,500 patients-per-physician ratio often previously cited as the standard for panel size.29 However, research has found that PCPs would have to work 21.7 hours per day to maintain a patient panel size of 2,500, and actual patient panel sizes range from 1,200 to 1,900.30 Further, the number of Americans with a PCP has been falling; currently only two-thirds of Americans have access to a “usual source of primary care;”31 the issue is much more pronounced in the younger adult population.32 Although younger adults do not typically command a large portion of the medical services (and thus care coordination services), this may indicate looming difficulties in the future if there is no PCP quarterback to make the aforementioned specialist referral or help oversee a care coordination team.

A recent study found that “PCPs do not have enough time to provide the guideline-recommended primary care,”33 corroborating the concerns of industry stakeholders. Consequently, it is reasonable to assume that if PCPs do not have adequate time to spend with their patients, they likely do not have the requisite amount of time to devote to the care coordination services that will result in high-quality care.

In order to ameliorate the primary care shortage and meet the growing demand for healthcare services, healthcare organizations are increasingly relying upon non-physician, advanced practice providers (APPs) such as nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs), in soliciting a vertical expansion in the role of the non-physician workforce to provide services that supported, supplemented, and paralleled physician services. In light of the fact that the gap between the supply and demand for physician services is increasing as the sources of physician manpower remain insufficient and the drivers of demand intensify, the APP workforce has seen continued growth in both scope and volume, as organizations adopt care models that strategically allocate physician and non-physician manpower resources. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, NP job growth is expected to be 35%, and PA job growth is expected to be 20%, from 2024 to 2034, far exceeding the 3% average growth rate for all occupations.34

Conclusion

In order to meet the growing demand for healthcare services – driven by the shift to value-based care, aging population, and rising prevalence of chronic diseases – amidst a primary care shortage that is resulting in a shortage in the sheer number of PCPs, as well as in the amount of time available to devote to the tasks involved in a primary-to-specialist care referral, the outsourcing of care coordination services to other medical staff members and/or through the utilization of care coordination software may be necessary in order to free up the clinician to focus on treating the patient. Accordingly, the next installment in this five-part series will explore the technological advancements supporting care coordination.

“Patient, PCP, and specialist perspectives on specialty care coordination in an integrated health care system” By Varsha Vimalananda, MD, MPH, et al., Journal of Ambulatory Care Management (January 1, 2019), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5726433/ (Accessed 9/18/25).

“Care Fragmentation, Quality, and Costs Among Chronically Ill Patients” By Brigham R. Frandsen, PhD, et al., The American Journal of Managed Care, Vol. 21, Issue 5 (May 2015), https://www.ajmc.com/view/care-fragmentation-quality-costs-among-chronically-ill-patients (Accessed 9/18/25).

“Care Management: It’s More than Population Health” Frost & Sullivan, 2017, https://www.experian.com/content/dam/marketing/na/healthcare/white-papers/frost-sullivan-care-management-population-health-outcomes.pdf (Accessed 9/18/25).

“Healthcare Industry Forecast: High Demand Due to Aging, Economy” AMN Healthcare, 2020, https://www.amnhealthcare.com/latest-healthcare-news/healthcare-industry-forecast/ (Accessed 9/18/25).

“Actualizing Better Health And Health Care For Older Adults” By Terry Fulmer, et al., Health Affairs, Vol. 40, No. 2 (January 2021), https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.01470 (Accessed 9/18/25).

“Per person personal health care spending for the 65 and older population was $22,356 in 2020, over 5 times higher than spending per child ($4,217) and almost 2.5 times the spending per working-age person ($9,154).” “NHE Fact Sheet” Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NHE-Fact-Sheet (Accessed 9/18/25).

“1: Chronic Conditions Among Older Americans” in “Chronic Care: A Call to Action for Health Reform” American Association of Retired Persons, http://assets.aarp.org/rgcenter/health/beyond_50_hcr_conditions.pdf (Accessed 9/18/25), p. 15.

“About Chronic Diseases” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, October 4, 2024, https://www.cdc.gov/chronic-disease/about/index.html (Accessed 9/18/25).

“Chronic Disease Prevalence in the US: Sociodemographic and Geographic Variations by Zip Code Tabulation Area” By Gabriel A. Benavidez, PhD, et al., Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Preventing Chronic Disease, February 29, 2024, https://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2024/23_0267.htm (Accessed 9/18/25).

“Get the Facts on Healthy Aging” National Council on Aging, August 16, 2024, https://www.ncoa.org/article/get-the-facts-on-healthy-aging (Accessed 9/18/25).

“BRFSS Prevalence & Trends Data” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/brfssprevalence/index.html (Accessed 9/18/25).

“Hospitalization” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/hus/topics/hospitalization.htm#explore-data (Accessed 9/18/25).

“Trends in Emergency Department Use by Rural and Urban Populations in the United States” By Margaret B. Greenwood-Ericksen, MD, MSc and Keith Kocher, MD, MPH, Jama Network Open, April 12, 2019, https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2730472 (Accessed 9/18/25), p. 1.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, October 4, 2024.

“Experiences of care coordination among older adults in the United States Evidence from the Health and Retirement Study” By Marisa R. Eastman, et al., Patient Education Counseling, Vol. 105, No. 7 (2022), https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9203919/ (Accessed 9/17/25).

“The Importance of Coordinated Care for Seniors” LTC News, February 21, 2023, https://www.ltcnews.com/articles/importance-of-coordinated-care-for-seniors (Accessed 9/18/25).

“Function of the Medical Team Quarterback: Patient, Family, and Physician Perspectives on Team Care Coordination in Patient- and Family-Centered Primary Care” By Marlaine Figueroa Gray, et al., The Permanente Journal, Vol. 23 (August 26, 2019), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6730945/ (Accessed 10/13/21).

“Mastering care coordination” By Rachel Zimlich, RN, Medical Economics Journal, Vol. 97, Issue 9 (May 2020), https://www.medicaleconomics.com/view/mastering-care-coordination (Accessed 11/3/21).

“The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections from 2018 to 2033” Association of American Medical Colleges, June 2020, p. vii.

“The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections from 2013 to 2025” IHS Inc., Report for the Association of American Medical Colleges, March 2015, p. 52-53.

“IBISWorld Industry Report 62111b: Specialist Doctors in the US” By Anna Miller, IBIS World, October 2020, p. 13.

“Primary Care in the United States: Past, Present and Future” By Edward P. Hoffer, MD, FACP, FACC, The American Journal of Medicine, https://www.amjmed.com/article/S0002-9343(24)00163-3/fulltext (Accessed 9/18/25).

“IBISWorld Industry Report 62111a: Primary Care Doctors in the US” By Kelsey Oliver, IBIS World, December 2018, p. 14.

“The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections From 2019 to 2034” Association of American Medical Colleges, June 2021, p. 7.

“U.S. Physician Workforce Data Dashboard” Association of American Medical Colleges, https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/report/us-physician-workforce-data-dashboard (Accessed 9/18/25).

“A Primary Care Panel Size of 2500 Is neither Accurate nor Reasonable” By Melanie Raffoul, Miranda Moore, Doug Kamerow, and Andrew Bazemore, Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, Vol. 29, No. 4 (July 2016), p. 496-497.

“Closing the Primary Care Gap” National Association of Community Health Centers, February 2023, https://www.nachc.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Closing-the-Primary-Care-Gap_Full-Report_2023_digital-final.pdf (Accessed 9/18/25).

“Declining numbers of Americans have a primary care provider” By Linda Carroll, Reuters, December 16, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-pcp-trends/declining-numbers-of-americans-have-a-primary-care-provider-idUSKBN1YK1Z4 (Accessed 9/18/25).

“Revisiting the Time Needed to Provide Adult Primary Care” By Justin Porter, et al., Journal of General Internal Medicine, Vol. 38, No. 1 (2022), https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9848034/ (Accessed 9/18/25).

“Occupational Outlook Handbook: Nurse Anesthetists, Nurse Midwives, and Nurse Practitioners” Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor, https://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/nurse-anesthetists-nurse-midwives-and-nurse-practitioners.htm (Accessed 9/18/25); “Occupational Outlook Handbook: Physician Assistants” Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor, https://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/physician-assistants.htm (Accessed 9/18/25).