With the emergence of value-based reimbursement, such as accountable care organizations (ACOs), clinically integrated networks (CINs), and bundled payment models, which rely on achieving the “Triple Aim” of healthcare at lower cost, U.S. hospitals are increasingly looking to change how services are being delivered by seeking more collaborative relationships with physicians, including vertical integration strategies such as the acquisition of healthcare-related enterprises, assets, and services (e.g., physician practices), direct employment, co-management, and joint venture arrangements with physicians and other providers.

The rise of these emerging healthcare organizations (EHOs) to address value-based reimbursement has led to a growing number and complexity of transactions in the healthcare delivery marketplace, accompanied by increased federal and state regulatory scrutiny regarding the legal permissibility of these arrangements. Most notably, government regulators (more specifically, the Office of the Inspector General [OIG] of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [HHS], and the U.S. Department of Justice [DOJ]) have, in some cases, more aggressively challenged an increasing array of these transactions under various federal and state fraud and abuse laws.

Therefore, now more than ever, conducting a level of due diligence appropriate to the scope and complexity of a given assignment is critical to the development of the valuation opinion. First and foremost, the appraiser serves in the role of a proxy for the universe of typical investors and buyers inherent in the requisite hypothetical transaction of the fair market value standard, which standard may not be exceeded in order to withstand regulatory scrutiny.

Due diligence may be defined as:

“such a measure of prudence, activity, or assiduity, as is properly to be expected from, and ordinarily exercised by, a reasonable and prudent man under the particular circumstances; not measured by any absolute standard, but depending on the relative facts of the special case”;

1

“

a fact-finding project….designed to find hidden risks”;

2 and,

“

an investigation in order to support the purchase price of the business.”

3

There are two distinct classes of information generally required for due diligence related to healthcare valuation: (1) general research; and, (2) specific research.

General research is typically comprised of information and data related to national and regional healthcare industry trends; reimbursement trends; competitive marketplace assessments; medical industry specialty and technological trends; transactional data; and, investment risk/return data, as well as, other research not specifically related to, or obtained from, the subject enterprise, asset, or service being appraised. General research is obtained for the purpose of providing a context within which the analyst considers the specific research and information gathered.

Specific research is related to information specific to the historical operational performance and financial condition of the subject enterprise, asset, or service, as well as, the pertinent clinical related data. Specific research is typically obtained from the client or the appropriate contact designated by the client.

In conducting the general and specific research required for the due diligence process, the analyst must develop an understanding of the market forces and the stakeholders that have the potential to drive healthcare markets. It is useful to examine what value relates to the four paramount market influences of the healthcare industry, i.e., the Four Pillars of healthcare – reimbursement, regulatory, competition, and technology.4 These four elements of the healthcare industry marketplace shape the dynamic by which providers and enterprises operate within the current transactional environment, while also serving as a conceptual framework for analyzing the viability, the efficiency, the efficacy, and, ultimately, the value that may be attributed to property interests, whether enterprises, assets, or services.

General research may be attained from a variety of sources, including:

Books and monographs;

Journals and periodicals;

Government agencies;

Proprietary data aggregators and portals;

Professional societies and trade associations;

Conferences and webinars;

Online databases; and,

Academic and industry “think tanks” and research foundations.

While the process of obtaining general research provides the valuation analyst with an adequate grasp of the body of knowledge applicable to a particular property interest being appraised, it is the efficacy of the valuation analyst’s subsequent application of generally accepted analytical methods to that data that determines the successful outcome of the assignment. The technical tools that the valuation analyst needs to employ to provide clients with the observations, findings, conclusions, and opinions that are to be deliverable under a particular engagement involves the synthesis of a substantial amount of data that may be pertinent to the valuation assignment, as well as the appropriate analysis, calculations, and considerations of the various types and forms of that data. Among the technical tools available to analysts is the benchmarking process, i.e., a comparison of specific research data from the subject property interest to industry indicated normative benchmark data, and may include the performance of a simple variance analysis on a single characteristic, such as a patient outcome metric related to “readmission within 30 days of discharge,” or may be comprehensive in scope, including the comparison of numerous clinical, operational, and financial metrics.

Benchmarking is used to establish an understanding of the operational and clinical performance, and financial status of a healthcare enterprise. Benchmarking techniques can also be utilized to illustrate the degree to which an organization diverges from comparable healthcare industry norms, as well as, providing vital information regarding trends within the organization’s internal operational performance and financial status. For example, benchmarking in the healthcare services sector serves several purposes:

Offers insight into the enterprise and practitioner performance as it relates to the rest of the market (e.g., allowing organizations to find where they “rank” among competitors, and as a means for continuous quality improvement);

Objectively evaluates performance indicators on the enterprise and practitioner levels;

Indicates variability, extreme outliers, and prospects;

Identifies areas that require further attention and possible remediation (e.g., re-distributing resources and staff, and increasing operating room utilization);

Promotes quality and efficiency improvement (e.g., improving average length of stay and other clinical efficiency measures); and,

Provides enterprises with a value-metric system to determine if they comply with legal standards for

fair market value and

commercial reasonableness.

5

In contrast to general research, specific research is information and data that is directly related to, or obtained from, the subject enterprise, asset, or service being valued. Specific research will often be comprised primarily of those documents received by the valuation analyst through the information and data gathering process (or discovery process in the case of litigation support engagements) including, but not limited to, preliminary legal/organizational and transactional documents, so that any material compliance issues may be identified. A sample of some of the requested preliminary legal/organizational and transactional documents in a healthcare transaction due diligence process are as follows:

Legal/Organizational Documents:

Articles of Incorporation, LLC Formation Agreements, Partnership Certifications, Certificates of Trust;

Bylaws, Operating Agreements, Trust Agreements;

Shareholder Agreements, Member Agreements, Partnership Agreements;

Pertinent Executive Meeting Minutes;

Existing Employment Agreements and Curriculum Vitae for Key Personnel;

Real Property Lease Agreements;

Personal Property Lease Agreements;

Existing Buy-Sell Agreements;

Existing Consulting or Management Services Agreements;

Loan Agreements;

Related Party Vendor/Supplier Agreements;

Third Party Payor Agreements;

Transactional Documents:

Asset Purchase Agreements;

Stock Purchase Agreements;

Bills of Sale;

Asset Contribution Agreements;

Buy-Sell Agreements;

Standstill Agreements;

Non-Disclosure & Confidentiality Agreement;

Letters of Intent;

Transaction Term Sheets;

Proposed Employment Agreements;

Proposed Lease Agreements; and,

Proposed Compensation Plan Details.

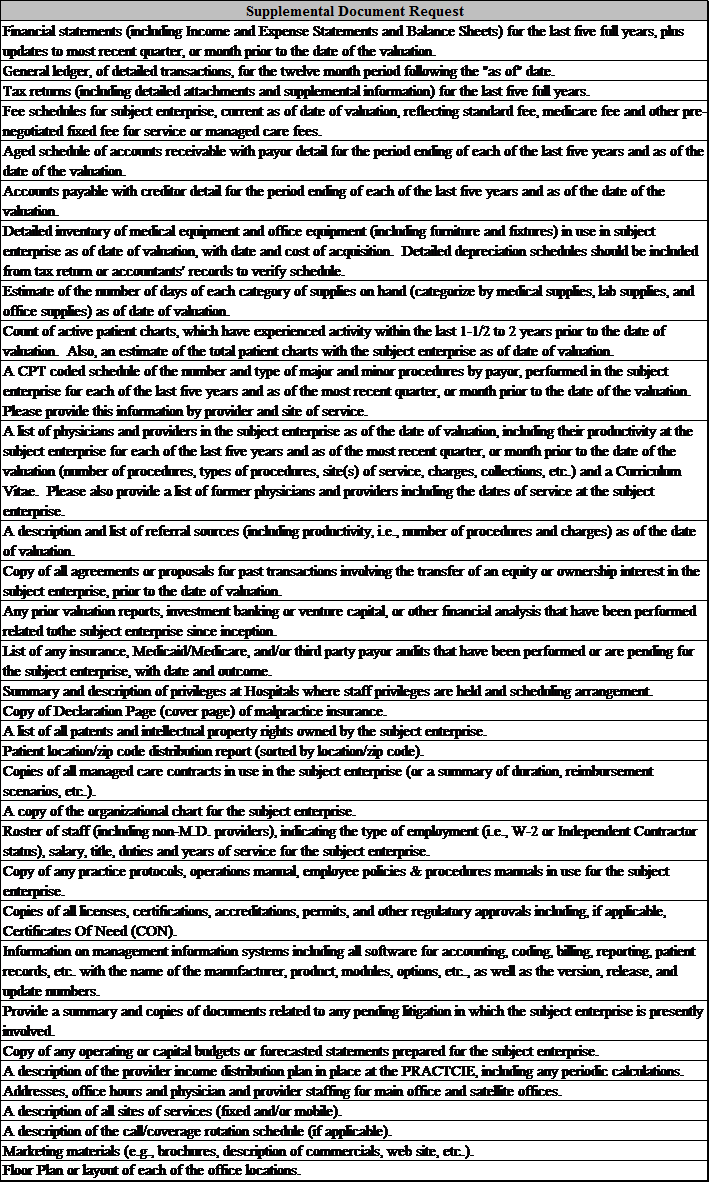

Upon the valuation professional’s review and analysis of the preliminary documents and information provided, a customized supplemental request for documents and information should be developed in consideration of the unique attributes and circumstances in the healthcare transaction, including, but not limited to, the items set forth in Table 1, below.

Additional subject-specific information may also be obtained through the site visit/management interview. Some of the types of subject-specific information that may be collected during the site visit/management interview is listed below:

History and Background Information;

Premise/Location/Building Description;

Transition to Electronic Medical Records;

Quality of Staff and Depth of Management;

Competitive Trend Analysis;

Patient Base Trends;

Managed Care Environment;

Hospital Privileges and Facilities;

Referral Sources and Patterns;

Strength of Financial Management and Credit Collections Policy;

Operational Efficiency Assessment; and,

Future Plans, e.g., Growth, Transition to Value-Based Reimbursement.

As part of the requisite due diligence associated with a specific engagement, the valuation analyst should conduct independent research, specific to the subject enterprise, to supplement any information provided by the subject entity; in line with the old Russian proverb, “Trust but Verify.”6 For example, the valuation analyst may conduct a Uniform Commercial Code (UCC) search to determine if the subject enterprise has any undisclosed outstanding liabilities or whether the subject enterprise leases, rather than owns, their tangible personal property, i.e., furniture, fixtures, and equipment. Similarly, a search for filings related to the subject enterprise with the Office of the Secretary of State in which the subject enterprise operates should be performed to identify pertinent information related to the actual legal organization of the subject enterprise, as well as, performing a brief search of online legal databases, such as Public Access to Court Electronic Records7 for federal litigation, and state litigation databases, such as Case.net8 in Missouri, to reveal any past and ongoing litigation involving the subject property interest, including shareholder disputes, commercial damages and liabilities, and malpractice cases. Further information related to the subject enterprise, asset, or service, which might not have been disclosed, may be gleaned from state licensing and certifying agencies and disciplinary boards, and may have an impact on the reputation, as well as the clinical and operational performance and financial status of the subject enterprise. It should be noted that subsequent events, i.e., events that would not have been known or knowable as of the valuation date, but which may also have a deleterious effect on the value indication for the subject property, must be disclosed, within the valuation report, to the client. However, these subsequent events do not have an impact on the valuation opinion, as of the valuation date, and may require a decision by the client whether an updated valuation report, i.e., with a valuation date after the subsequent events, should be undertaken.

The valuation analyst should also restate and adjust the subject enterprise specific financial data received to: (1) facilitate industry benchmark comparisons of the specific line item allocations of the subject entity’s financial statements to comparable industry indicated benchmark norms for those line items; and, (2) reflect the true economic operating performance and financial status of the subject enterprise. Accordingly, the valuation analyst should carefully consider restating certain line items related to the revenue and expenses of the subject entity, e.g., owner compensation and benefits; discretionary expenses not required to support the projected revenue of the subject enterprise; and, extraordinary non-operating income and expenses. Likewise, the valuation analyst should consider restating certain of the assets and liabilities of the subject entity, e.g., remove non-operating assets; adjust tangible personal property (i.e., furniture, fixtures, and equipment) from book value to economic fair market value; and, removing those assets excluded from the property interest being appraised, such as accounts receivable and cash.

The next step in the due diligence process is to determine the extent and the probability of the continuity of the subject business’ benefit stream and competitive advantage into the future. A valuation analyst who leads such a process must follow three credos to “discover the truth”:

“Be Skeptical” – Do not believe what you read or what people tell you, or at least be aware of the biased information you are receiving. Always seek corroborative evidence;

“D&D: Disclose and Disclaim” – The due diligence process is, by its very nature, a documentation-intensive engagement. In addition to maintaining an organized filing system, it is important to disclose all findings, even those to be deemed immaterial; and,

“Follow the Scientific Method” – Although there is an art to this work, a successful due diligence process uses the scientific method. In the world of due diligence it truly can be stated that “the product is the process.” The successful valuation analyst will generate hypotheses, establish method(s), test hypotheses, report results, and develop conclusions in an orderly, documented, and replicable manner. In keeping with the philosophy of scientific research, due diligence must be objective in its approach and conduct.