As discussed in the first installment of this three-part series on the valuation of anesthesiology services, despite the increasing demand for anesthesiology providers, Medicare reimbursement for anesthesiology has decreased over the past few years. Additionally, like other healthcare providers, anesthesiology clinicians face a range of federal and state legal and regulatory constraints that affect their formation, operation, procedural coding and billing, and transactions. Consequently, this second installment will review the reimbursement and regulatory landscapes in which these anesthesiology providers operate.

Reimbursement Environment

The U.S. government is the largest payor of medical costs, through Medicare and Medicaid, and has a strong influence on reimbursement to hospitals. In 2023, Medicare and Medicaid accounted for an estimated $1.030 trillion and $871.7 billion in healthcare spending, respectively.1 The prevalence of these public payors in the healthcare marketplace often results in their acting as a price setter, and being used as a benchmark for private reimbursement rates.

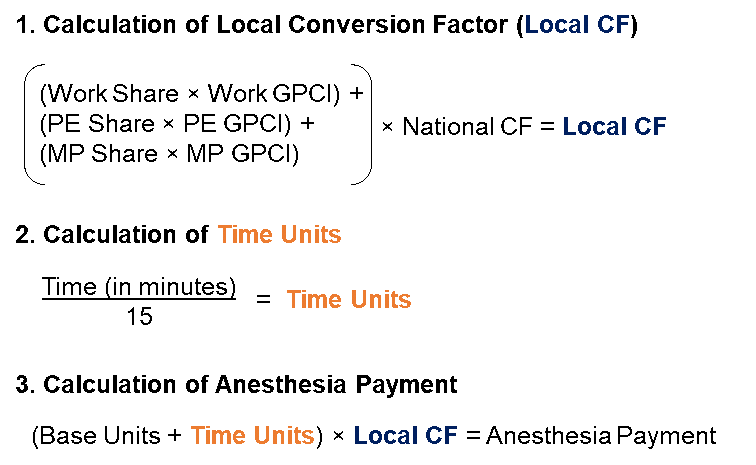

Medicare reimburses providers for anesthesiology services under the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (MPFS), but these services are reimbursed differently from other physician services. The MPFS assigns each procedure a number of base units and time units. A base unit represents the complexity of a surgery and associated anesthesia service costs and is assigned to each anesthesia CPT code.2 Notably, the base units have not been changed since 2022.3 Time units are calculated by dividing the length of time the patient was under anesthesia by 15.4 The base units and the time units are then summed and multiplied by a conversion factor (CF), which is different from the MPFS relative value unit (RVU) CF.5 The CF varies based on the location of the procedure, and is calculated by multiplying the national CF by a weighted average of the area’s Geographic Practice Cost Index (GPCI) for labor (work) costs, practice (PE) expense, and malpractice (MP) expense.6 In this way, payments can be adjusted to suit the cost of providing services in a particular geographic area.

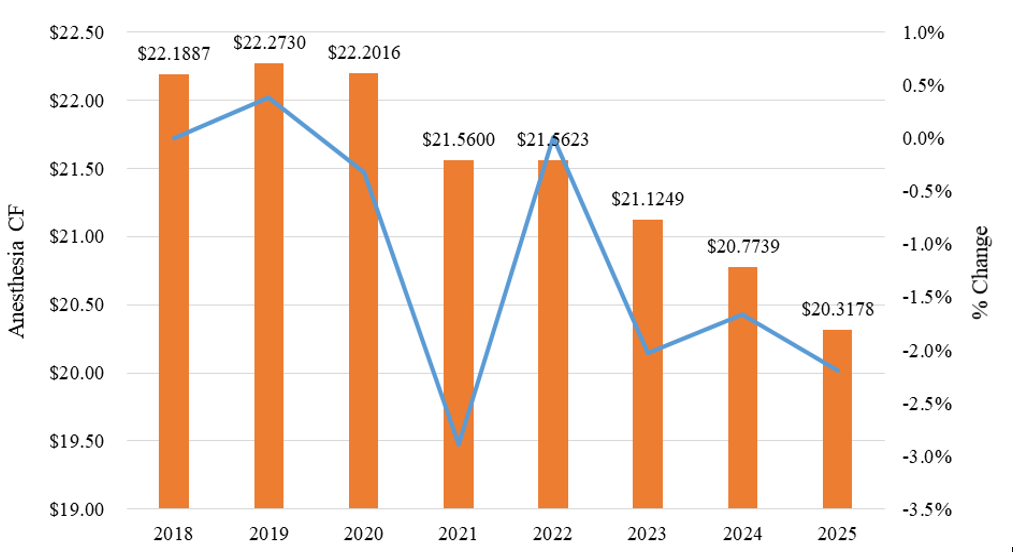

Since 2018, the national anesthesia CF has decreased significantly (-8.43%). Exhibit 1 below sets forth the historical Medicare anesthesia CF amounts.

The process by which the local CF, time units, and payment for anesthesiology services is calculated is illustrated in the below Exhibit 2.

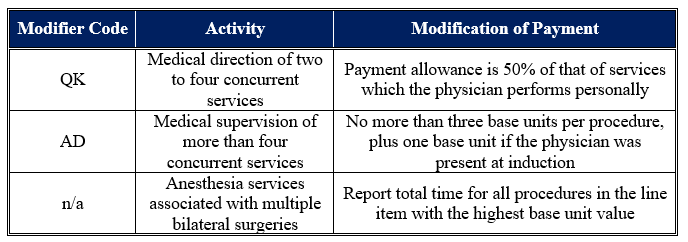

Notably, Exhibit 2 does not include modifiers. Some modifiers can change the payments that Medicare makes to an anesthesiologist. These modifiers are described in Table 1 below.

Medicare also reimburses nonphysician practitioners who provide anesthesia services, referred to as qualified nonphysician anesthetists, including Certified Registered Nurse Anesthetists (CRNAs) and Anesthesiologist Assistants (AAs).8 These providers are reimbursed under the same methodology as physician anesthesiologists; CRNAs are reimbursed at the same rate as physicians, but AAs are reimbursed at 85% of the physician payment rate.9 If a physician and CRNA are both involved in an anesthesia procedure, each receives 50% of the payment.

Regulatory Environment

Regulatory security has generally increased for healthcare providers over the last decade. Fraud and abuse laws, specifically those related to the federal Anti-Kickback Statute (AKS) and physician self-referral laws (the Stark Law), have significant impact on the operations of anesthesiology providers.

The AKS and Stark Law are generally concerned with the same issue – the financial motivation behind patient referrals. However, while the AKS is broadly applied to payments between providers or suppliers in the healthcare industry and relates to any item or service that may be paid for under any federal healthcare program, the Stark Law specifically addresses the referrals from physicians to entities with which the physician has a financial relationship for the provision of defined services that are paid for by the Medicare program.10 Additionally, while violation of the Stark Law carries only civil penalties, violation of the AKS carries both criminal and civil penalties.11

Anti-Kickback Statute

Enacted in 1972, the federal AKS makes it a felony for any person to “knowingly and willfully” solicit or receive, or to offer or pay, any “remuneration”, directly or indirectly, in exchange for the referral of a patient for a healthcare service paid for by a federal healthcare program,12 even if only one purpose of the arrangement in question is to offer remuneration deemed illegal under the AKS.13 Notably, a person need not have actual knowledge of the AKS or specific intent to commit a violation of the AKS for the government to prove a kickback violation,14 only an awareness that the conduct in question is “generally unlawful.”15 Further, a violation of the AKS is sufficient to state a claim under the False Claims Act (FCA).16

Criminal violations of the AKS are punishable by up to ten years in prison, criminal fines up to $100,000, or both, and civil violations can result in administrative penalties, including exclusion from federal healthcare programs, and civil monetary penalties plus treble damages (or three times the illegal remuneration).17 In addition to the civil monetary penalties paid under the AKS, if the AKS violation triggers liability under the FCA, defendants can incur additional per-violation civil monetary penalties plus treble damages.18

Due to the broad nature of the AKS, legitimate business arrangements may appear to be prohibited.19 In response to these concerns, Congress created a number of statutory exceptions and delegated authority to the Department of Health & Human Services (HHS) to protect certain business arrangements by means of promulgating several safe harbors.20 These safe harbors set out regulatory criteria that, if met, shield an arrangement from regulatory liability, and are meant to protect transactional arrangements unlikely to result in fraud or abuse.21 Failure to meet all of the requirements of a safe harbor does not necessarily render an arrangement illegal.22 It should be noted that, in order for a payment to meet the requirements of many AKS safe harbors, the compensation must not exceed the range of Fair Market Value and must be commercially reasonable.

Stark Law

The Stark Law prohibits physicians from referring Medicare patients to entities with which the physicians or their family members have a financial relationship for the provision of designated health services (DHS).23 Further, when a prohibited referral occurs, entities may not bill for services resulting from the prohibited referral.24 Under the Stark Law, DHS include, but are not limited to, the following:

Inpatient and outpatient hospital services;

Radiology and certain other imaging services;

Radiation therapy services and supplies;

Certain therapy services, such as physical therapy;

Durable medical equipment; and,

Outpatient prescription drugs.

25

Under the Stark Law, financial relationships include ownership interests through equity, debt, other means, and ownership interests in entities also have an ownership interest in the entity that provides DHS.26 Additionally, financial relationships include compensation arrangements, which are defined as arrangements between physicians and entities involving any remuneration, directly or indirectly, in cash or in kind.27

Civil penalties under the Stark Law include overpayment or refund obligations, a potential civil monetary penalty of $15,000 for each service, plus treble damages, and exclusion from Medicare and Medicaid programs.28 Further, similar to the AKS, violation of the Stark Law can also trigger a violation of the FCA.29

Notably, the Stark Law contains a large number of exceptions, which describe ownership interests, compensation arrangements, and forms of remuneration to which the Stark Law does not apply.30 Similar to the AKS safe harbors, without these exceptions, the Stark Law may prohibit legitimate business arrangements. It must be noted that in order to meet the requirements of many exceptions related to compensation between physicians and other entities, compensation must: (1) not exceed the range of fair market value; (2) not take into account the volume or value of referrals generated by the compensated physician; and, (3) be commercially reasonable. Unlike the AKS safe harbors, an arrangement must fully fall within one of the exceptions in order to be shielded from enforcement of the Stark Law.31

The reimbursement and regulatory landscape for anesthesiology services presents a complex web of challenges that significantly impact providers and their operational viability. While Medicare's continued dominance as a price-setter creates predictable revenue streams, the 8.43% decline in the national anesthesia CF since 2018 underscores mounting financial pressures that anesthesiology providers must navigate. Simultaneously, the heightened enforcement environment surrounding the AKS and Stark Law demands sophisticated compliance frameworks that can substantially affect operational costs and transaction structures. These dual pressures—declining reimbursement coupled with increasing regulatory scrutiny—create a need for reliance on emerging technological innovations in anesthesia delivery in order to survive. The last installment in this three-part series will discuss the technological advancements transforming the delivery of anesthesiology services.

“NHE Fact Sheet” Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, December 18, 2024, https://www.cms.gov/data-research/statistics-trends-and-reports/national-health-expenditure-data/nhe-fact-sheet (Accessed 1/16/25).

“Anesthesia Base Units” U.S. Department of Labor, https://owcpmed.dol.gov/ecams/help/WebHelp/HTML5/Content/Rate_Settings/Anesthesia_Base_Units.htm#:~:text=They%20represent%20the%20amount%20of,time%20in%20the%20operating%20room. (Accessed 1/17/25).

“Anesthesiologists Center’ Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, https://www.cms.gov/medicare/payment/fee-schedules/physician/anesthesiologists-center (Accessed 1/16/25).

“Physician and other Health Professional Payment System” Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, Payment Basics, October 2024, available at: https://www.medpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/MedPAC_Payment_Basics_24_Physician_FINAL_SEC.pdf (Accessed 1/16/25).

“Locality-Adjusted Anesthesia Conversion Factors as a result of the CY 2025 Final Rule” in “Anesthesia CY 2025 locality adjusted CF_floor extension 23DEC24.xlsx” available at: https://www.cms.gov/files/zip/2025-anesthesia-conversion-factors.zip (Accessed 1/16/25).

“50 – Payment for Anesthesiology Services” in “Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12 – Physicians/Nonphysician Practitioners” Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, December 19, 2024, https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf (Accessed 1/16/25).

“140.1 – Qualified Nonphysician Anesthetists” in “Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12 – Physicians/Nonphysician Practitioners” Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, December 19, 2024, https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf (Accessed 1/16/25).

Letter from American Association of Nurse Anesthesiology to Chiquita Brooks-LaSure RE: Request for Information on Medicare, dated August 24, 2022, available at: https://bettermedicarealliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/American-Association-of-Nurse-Anesthesiology.pdf (Accessed 1/16/25).

“Comparison of the Anti-Kickback Statute and Stark Law” Health Care Fraud Prevention and Enforcement Action Team (HEAT) Office of Inspector General (OIG), https://oig.hhs.gov/documents/provider-compliance-training/939/StarkandAKSChartHandout508.pdf (Accessed 8/14/23).

“Criminal Penalties for Acts Involving Federal Health Care Programs” 42 USC § 1320a-7b(b)(1).

“Re: OIG Advisory Opinion No. 15-10” By Gregory E. Demske, Chief Counsel to the Inspector General, Letter to [Name Redacted], July 28, 2015, https://oig.hhs.gov/fraud/docs/advisoryopinions/2015/AdvOpn15-10.pdf (Accessed 8/14/23), p. 4-5; “U.S. v. Greber” 760 F.2d 68, 69 (3d. Cir. 1985).

“Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act” Pub. L. No. 111-148, §§ 6402, 10606, 124 Stat. 119, 759, 1008 (March 23, 2010).

“Health Care Fraud and Abuse Laws Affecting Medicare and Medicaid: An Overview” By Jennifer A. Staman, Congressional Research Service, September 8, 2014, https://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/RS22743.pdf (Accessed 8/14/23), p. 5.

“Health Care Reform: Substantial Fraud and Abuse and Program Integrity Measures Enacted” McDermott Will & Emery, April 12, 2010, p. 3; “Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act” Pub. L. No. 111-148, § 6402, 124 Stat. 119, 759 (March 23, 2010).

“Criminal Penalties for Acts Involving Federal Health Care Programs” 42 USC § 1320a-7b(b)(1); “Civil Monetary Penalties” 42 USC § 1320a-7a(a).

“False claims” 31 USC § 3729(a)(1)(G); “Civil Monetary Penalties Inflation Adjustments for 2023” Federal Register, Vol. 88, No. 19 (January 30, 2023), p. 5777.

Demske, Chief Counsel to the Inspector General, Letter to [Name Redacted], July 28, 2015.

“Medicare and State Health Care Programs: Fraud and Abuse; Clarification of the Initial OIG Safe Harbor Provisions and Establishment of Additional Safe Harbor Provisions Under the Anti-Kickback Statute; Final Rule” Federal Register Vol. 64, No. 223 (November 19, 1999), p. 63518, 63520.

“Re: Malpractice Insurance Assistance” By Lewis Morris, Chief Counsel to the Inspector General, United States Department of Health and Human Services, Letter to [Name redacted], January 15, 2003, https://oig.hhs.gov/fraud/docs/alertsandbulletins/malpracticeprogram.pdf (Accessed 8/14/23), p. 1.

“CRS Report for Congress: Medicare: Physician Self-Referral (“Stark I and II”)” By Jennifer O’Sullivan, Congressional Research Service, The Library of Congress, July 27, 2004, available at: http://www.policyarchive.org/handle/10207/bitstreams/2137.pdf (Accessed 8/14/23); “Limitation on certain physician referrals” 42 USC § 1395nn.

“Limitation on certain physician referrals” 42 USC § 1395nn(a)(1)(A).

“Limitation on Certain Physician Referrals” 42 USC § 1395nn(a)(1)(B); “Definitions” 42 CFR § 411.351 (2015). Note the distinction in 42 CFR § 411.351 regarding what services are included as DHS: “Except as otherwise noted in this subpart, the term ‘designated health services’ or DHS means only DHS payable, in whole or in part, by Medicare. DHS do not include services that are reimbursed by Medicare as part of a composite rate (for example, ASC services identified at §416.164(a)), except to the extent that services listed in paragraphs (1)(i) through (1)(x) of this definition are themselves payable through a composite rate (for example, all services provided as home health services or inpatient and outpatient hospital services are DHS).”

“Limitation on certain physician referrals” 42 USC § 1395nn (a)(2).

“Limitation on certain physician referrals” 42 USC § 1395nn (h)(1).

“Limitation on certain physician referrals” 42 USC § 1395nn (g).

Health Care Fraud Prevention and Enforcement Action Team (HEAT) Office of Inspector General (OIG).

“Limitation on certain physician referrals” 42 USC § 1395nn.

Health Care Fraud Prevention and Enforcement Action Team (HEAT) Office of Inspector General (OIG).