As the U.S. healthcare system continues to shift its reimbursement scheme from traditional fee-for-service (FFS) payment to value-based alternative payment models, one value-based alternative payment model that has gained popularity since its establishment by the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) is the accountable care organization (ACO).1 In general, the ACO model holds groups of healthcare providers responsible for the quality and cost of healthcare delivery provided to an ACO’s patient population.2 ACOs are controlled by the provider members who work together to control costs, improve quality, and coordinate care, and those that achieve the spending and quality targets designated by payors receive a share of the savings.3 Most ACOs adhere to one of three primary structures: (1) hospital-led; (2) physician-led; and (3) jointly-led.4 ACOs vary significantly in the services delivered to patients and the types of providers included in an ACO group, as well as in their range of capabilities, which may include care management, advanced analytics, and shared interdisciplinary decision making.5

On average, ACOs are associated with improved patient satisfaction and other patient-reported measures.6 Many of the gains related to ACOs are concentrated in high-need, high-cost populations.7 However, there is significant variance in ACO performance, with some ACOs achieving savings and others spending far more after formation.8

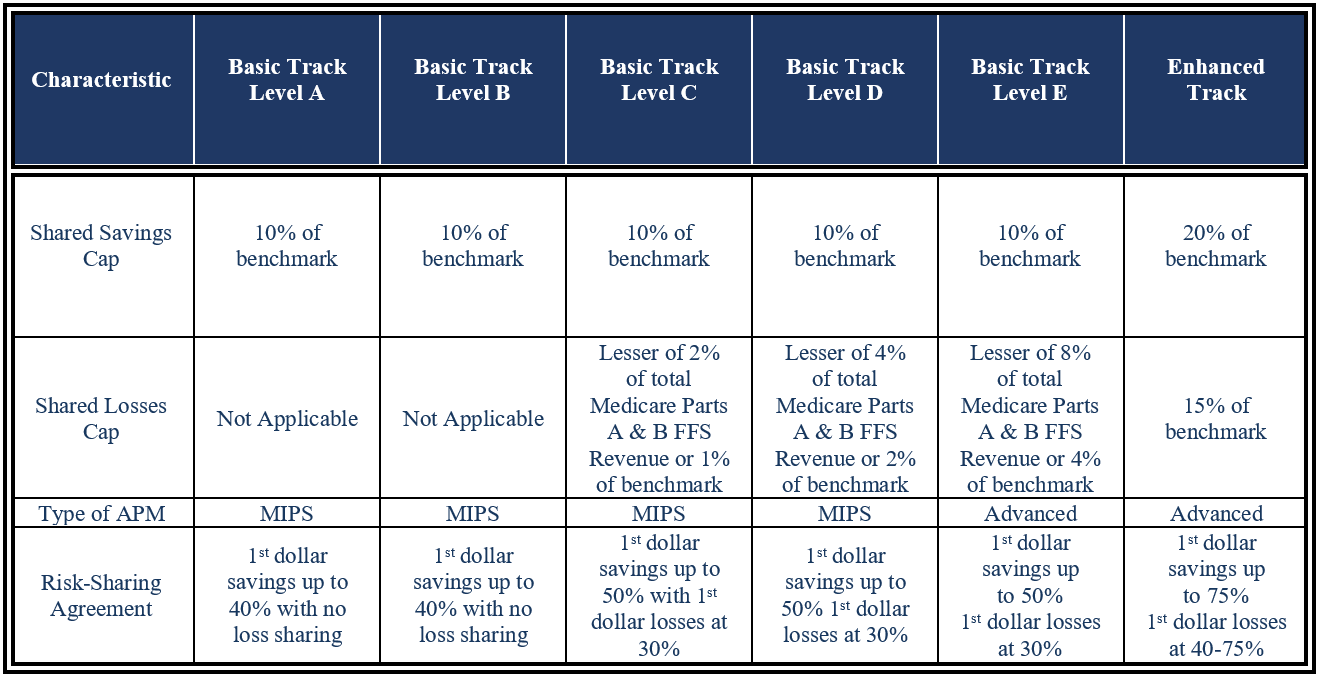

Most ACOs participate in government programs offered by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS).9 Currently, there are two CMS-run ACO models: (1) the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP) and (2) the Realizing Equity, Access, and Community Health (REACH) Model.10 As of 2023, 456 ACOs participated in the MSSP and 132 ACOs participated in the REACH Model.11 There are multiple MSSP participation options (tracks), split into Basic and Enhanced Tracks.12 The Basic Track is further divided into five track levels: A, B, C, D, and E.13 Financial risks associated with the different tracks are set forth below, in Table 1.

CMS’s determination of which ACO track applies to a participating ACO depends on the experience of ACO and whether the ACO is Low Revenue or High Revenue.15 High Revenue ACOs are ACOs with total Medicare FFS revenue of at least 35% of the total Medicare FFS expenditures for the ACO’s assigned beneficiaries.16 Low Revenue ACOs are any ACOs below this 35% threshold.17 This distinction in ACO revenue is important because High Revenue ACOs will be required to assume downside financial risk, as CMS assumes that High Revenue ACOs can control spending more efficiently, and thus can assume more financial risk.18

Further, as an ACO moves across the MSSP track levels and takes on more risk, there are a number of waivers and beneficiary incentives available. For example, the skilled nursing facility (SNF) three-day waiver eliminates the requirement for a three-day inpatient hospital stay prior to extended-care services provided to Medicare beneficiaries.19 The rule waiver allows for ACO participant hospitals to partner with SNFs to reduce inpatient costs. Additionally, the Beneficiary Incentive Program allows ACOs accepting downside financial risk to directly provide incentive payments up to $20 to Medicare beneficiaries to ensure beneficiaries have access to primary care resources.20

It is important to note that Advanced APM status is only available to the MSSP ACOs assuming downside risk.21 Providers who participate in an Advanced APM through the Quality Payment Program (QPP), which was established by the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA), do not have to participate in the QPP’s alternative program, the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS), which also has certain quality reporting requirements and resulting payment adjustments.22 Most importantly, participation in the Advanced APM program provides for an additional 5% incentive bonus for ACO providers.23

In 2022, CMS announced their redesign of the Global and Professional Direct Contracting (GPDC) Model to advance the agency’s priorities, e.g., advancing health equity.24 The GPDC Model was renamed ACO Realizing Equity, Access, and Community Health (REACH).25 The REACH Model focuses on changes in three important areas: (1) advancing health equity to ensure the benefits of ACOs reach underserved communities; (2) promoting governance and leadership by providers; and (3) vetting participants to protect beneficiaries of the program, greater overall transparency, and monitoring.26 The first performance year of this model began January 1, 2023.27

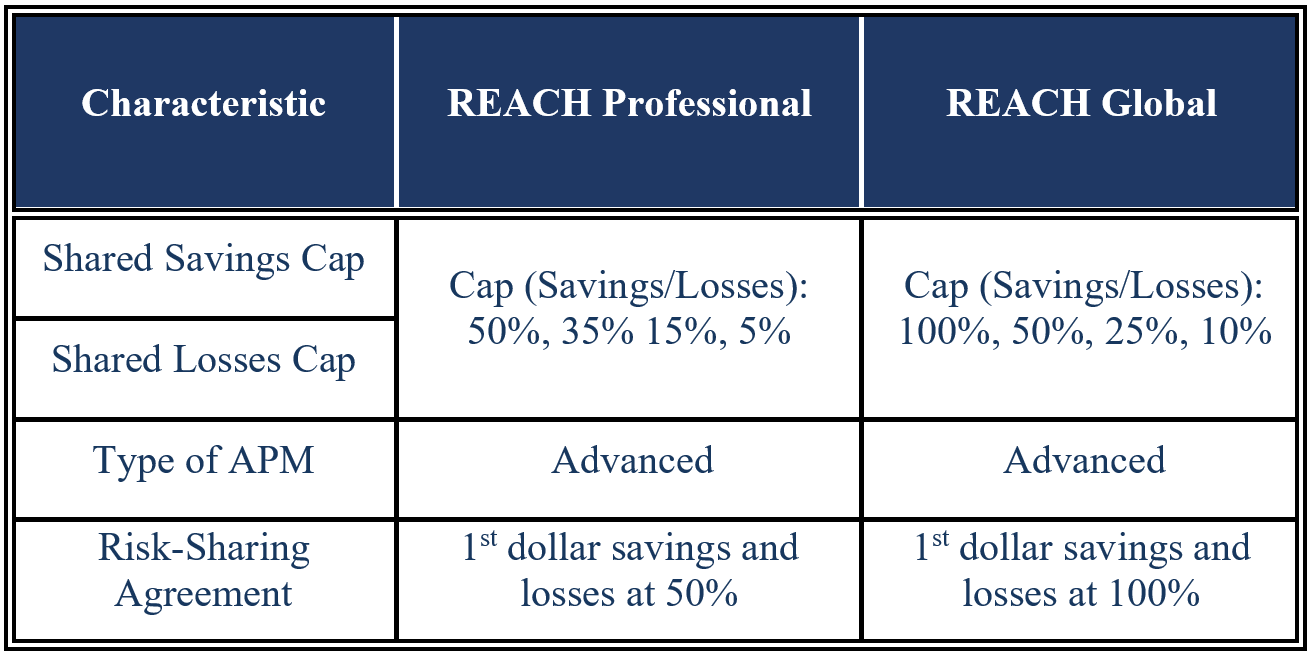

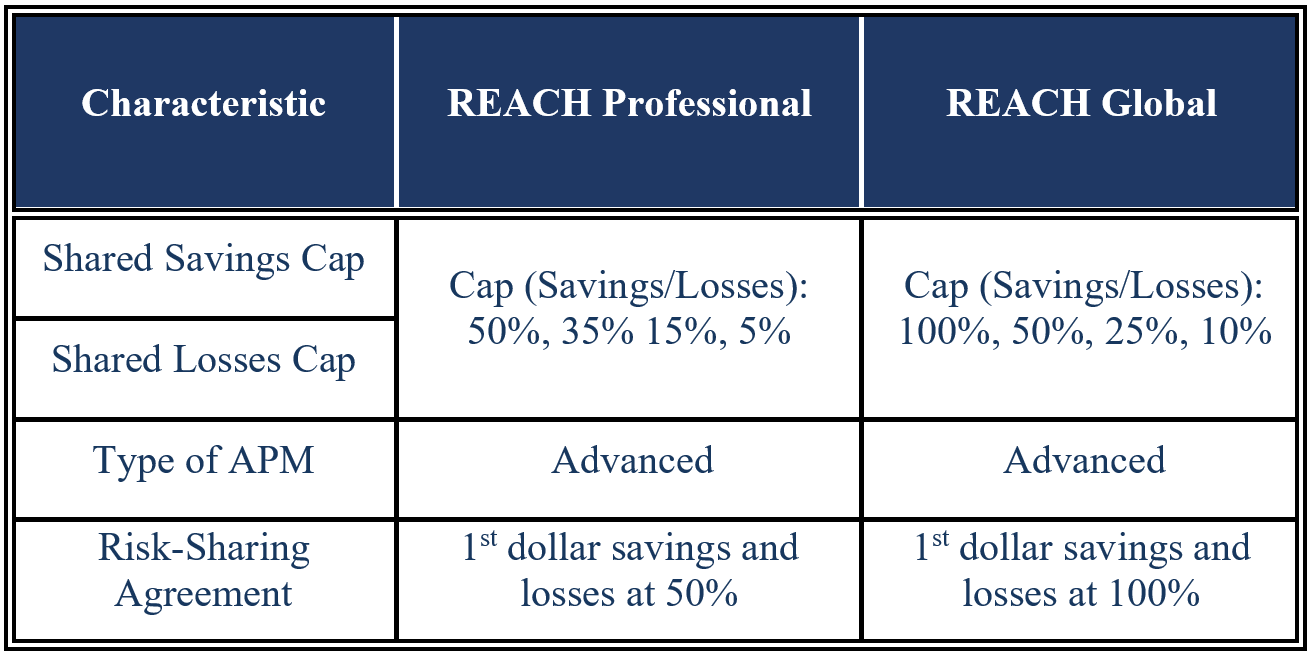

The model serves Standard ACOs, High Needs Population ACOs, and New Entrant ACOs.28 There are two voluntary risk options available, where providers receive ACO compensation because they accepted claims reductions from Medicare.29 The first risk option, the Professional Option, is lower risk, with 50% savings/losses and a risk-adjusted monthly payment, called the Primary Care Capitation Payment (PCCP), for the primary care services provided by ACO participants.30 The second option is a higher risk-sharing agreement, with 100% savings/losses, with two forms of payment: the PCCP or a Total Care Capitation Payment (TCCP), a risk-adjusted monthly payment for all services, including specialty care.31

Table 2: Comparison of ACO REACH Tracks32

Early estimates, which projected a rapid growth in the number of ACOs, missed the mark significantly. Initial estimates projected that ACOs would cover over 70 million people by 2020;33 however, as of 2019, ACOs only covered 44 million lives.34 Moreover, growth has slowed in recent years, driven by decreases in ACO contracts.35 Reductions in ACO contracts are primarily driven by providers’ reluctance to participate in ACO arrangements that involve downside risk.36 Many small- to medium-sized ACOs no longer see the value in participating in ACO contracts with Medicare,37 and primary care focused ACOs are moving to the other models offered by Medicare, such as the Primary Care First Model.38 However, many physician-led ACOs have remained in Medicare’s ACO programs despite increased downside risk, and more physician-led ACOs have chosen to take on downside risk compared to hospital-led ACOs.39 The trend may reflect the fact that physician-led ACOs significantly outperform hospital-led ACOs, making downside risk less of a concern.40 The second installment of this five-part series will cover the supply and demand driving the competitive environment of ACOs.

“Moving Forward with Accountable Care Organizations: Some Answers, More Questions” By Carrie H. Colla, JAMA Internal Medicine, Vol. 177, No. 4, April 2017, p. 527.

“Accountable Care Organizations — The Risk of Failure and the Risks of Success” By Lawrence P. Casalino, The New England Journal of Medicine, Vol. 371, Issue 18, October 2014, p. 1750; “Moving Forward with Accountable Care Organizations: Some Answers, More Questions” By Carrie H. Colla, JAMA Internal Medicine, Vol. 177, No. 4, April 2017, p. 527.

“Shared Savings Program” Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2023, https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/sharedsavingsprogram (Accessed 6/7/23).

“A taxonomy of accountable care organizations for policy and practice” By Stephen M. Shortell, et al., Health Services Research, Vol. 49, Issue 6, December 2014, p. 1883-1895; “Assessing Differences between Early and Later Adopters of Accountable Care Organizations Using Taxonomic Analysis” By Frances M. Wu, Stephen M. Shortell, Valerie A. Lewis, Carrie H. Colla, and Elliott S. Fisher, Health Services Research, Vol. 51, Issue 6, p. 2318-2329.

“First National Survey Of ACOs Finds That Physicians Are Playing Strong Leadership And Ownership Roles” By Carrie H. Colla, Valerie A. Lewis, Stephen M. Shortell, and Elliott S. Fisher, Health Affairs, Vol. 33, No. 6, June 2014, p. 967-970.

“Changes in Patients' Experiences in Medicare Accountable Care Organizations” By J. Michael McWilliams, Bruce E. Landon, Michael E. Chernew, and Alan M. Zaslavsky, The New England Journal of Medicine, Vol. 371, Issue 18, October 2014, p. 1715.

“Association Between Medicare Accountable Care Organization Implementation and Spending Among Clinically Vulnerable Beneficiaries” By Carrie H. Colla, Valerie A. Lewis, Lee-Sien Kao, et al, JAMA Internal Medicine, Vol. 176, Issue 8, August 2016, p. 1168; “Changes in Patients' Experiences in Medicare Accountable Care Organizations” By J. Michael McWilliams, Bruce E. Landon, Michael E. Chernew, and Alan M. Zaslavsky, The New England Journal of Medicine, Vol. 371, Issue 18, October 2014, p. 1715.

“Association of Pioneer Accountable Care Organizations vs Traditional Medicare Fee for Service With Spending, Utilization, and Patient Experience” By David J. Nyweide, Woolton Lee, Timothy T. Cuerdon, et al, JAMA, Vol. 313, Issue 21, June 2015, p. 2152-2161; “Association Between Medicare Accountable Care Organization Implementation and Spending Among Clinically Vulnerable Beneficiaries” By Carrie H. Colla, Valerie A. Lewis, Lee-Sien Kao, et al, JAMA Internal Medicine, Vol. 176, Issue 8, August 2016, p. 1167-1175.

“Moving Forward with Accountable Care Organizations: Some Answers, More Questions” By Carrie H. Colla, JAMA Internal Medicine, Vol. 177, No. 4, April 2017, p. 527.

“ACO Comparison Chart” National Association of Accountable Care Organizations, 2023, https://www.naacos.com/assets/docs/pdf/2023/ACO-ComparisonChart2023.pdf (Accessed 6/7/23).

“Shared Savings Program” Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2023, https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/sharedsavingsprogram/about (Accessed 6/7/23); “ACO REACH” Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, May 26, 2023, https://innovation.cms.gov/innovation-models/aco-reach (Accessed 6/9/23).

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2023.

National Association of Accountable Care Organizations, 2023.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2023.

“NAACOS Assessment of High-Low Revenue Designations” National Association of ACOs, 2020, https://www.naacos.com/naacos-assessment-of-high-low-revenue-designations (Accessed 6/9/23).

“Skilled Nursing Facility 3-Day Rule Waiver: Guidance” Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, May 2022, https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/sharedsavingsprogram/Downloads/SNF-Waiver-Guidance.pdf (Accessed 6/9/23), p. 1.

“Beneficiary Incentive Program” Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, May 2021, https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/sharedsavingsprogram/Downloads/BIP-guidance.pdf (Accessed 6/9/23).

“Advanced Alternative Payment Models (APMs)” Quality Payment Program, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2023, https://qpp.cms.gov/apms/advanced-apms (Accessed 6/9/23).

“Accountable Care Organization (ACO) Realizing Equity, Access, and Community Health (REACH) Model” Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, February 24, 2022, https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/accountable-care-organization-aco-realizing-equity-access-and-community-health-reach-model (Accessed 6/9/23).

“Accountable Care Organization (ACO) Realizing Equity, Access, and Community Health (REACH) Model” Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, February 24, 2022, https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/accountable-care-organization-aco-realizing-equity-access-and-community-health-reach-model (Accessed 6/9/23).

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, May 26, 2023.

National Association of Accountable Care Organizations, 2023.

“Growth And Dispersion Of Accountable Care Organizations In 2015” By David Muhlestein, Health Affairs, March 31, 2015, https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20150331.045829/full/ (Accessed 6/9/23).

“Spread of ACOs And Value-Based Payment Models In 2019: Gauging the Impact of Pathways to Success” By David Muhlestein, et al., Health Affairs, October 21, 2019, https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20191020.962600/full/ (Accessed 6/9/23).

“Primary Care First Model Options” Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2020, https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/primary-care-first-model-options/ (Accessed 6/9/23); “Spread of ACOs And Value-Based Payment Models In 2019: Gauging the Impact of Pathways to Success” By David Muhlestein, et al., Health Affairs, October 21, 2019, https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20191020.962600/full/ (Accessed 6/9/23).

Muhlestein, et al., Health Affairs, October 21, 2019.

“Medicare Spending after 3 Years of the Medicare Shared Savings Program” By J. Michael McWilliams, Laura A. Hatfield, Bruce E. Landon, Pasha Hamed, and Michael E. Chernew, The New England Journal of Medicine, Vol. 379, Issue 12, September 2018, p. 1139; “The 2018 Annual ACO Survey: Examining the Risk Contracting Landscape” By Robert Mechanic, et al., Health Affairs, April 23, 2019, https://www.healthaffairs.org/content/forefront/2018-annual-aco-survey-examining-risk-contracting-landscape (Accessed 6/22/23).