Introduction

This article is the second installment in a four-part series on valuation considerations for ambulatory surgery centers (ASCs) and office-based laboratories (OBLs), and the differences between these outpatient facilities. The first article in this series introduced the ASC and OBL industry, including reimbursement distinctions and the reasons behind the rapid growth of both enterprises over the past few decades.

At the same time that ASCs and OBLs were growing in both supply and in demand, increased regulatory scrutiny of the formation, ownership, alignment, and transactions related to these outpatient entities also grew. Consequently, it is important for those involved in any prospective transaction (or formation) to understand the regulatory environments in which both of these types of facilities operate, including a specific focus on the provisions of the Stark Law and Anti-Kickback Statue (AKS).

It should be noted that, in some cases, outpatient facilities are operated as a hybrid, wherein the facility is utilized for ASC procedures on some days, and for OBL procedures on other days. In these situations, the (more stringent) regulations related to ASCs would apply.

Stark Law

The Stark Law governs those physicians (or their immediate family members) who have a financial relationship (i.e., an ownership/investment interest or a compensation arrangement) with an entity, and prohibits those individuals from making Medicare referrals to those entities for the furnishing of designated health services (DHS).1 DHS encompasses the following items and services:

Clinical laboratory services;

Physical therapy services;

Occupational therapy services;

Radiology services, including magnetic resonance imaging, computerized axial tomography scans, and ultrasound services;

Radiation therapy services and supplies;

Durable medical equipment and supplies;

Parenteral and enteral nutrients, equipment, and supplies;

Prosthetics, orthotics, and prosthetic devices and supplies;

Home health services;

Outpatient prescription drugs;

Inpatient and outpatient hospital services; and,

Outpatient speech-language pathology services.

2

OBLs and ASCs are generally not subject to Stark Law restrictions because they typically do not furnish DHS. However, in the event that the ASC/OBL is performing DHS (e.g., radiology services), and that DHS is not reimbursed by Medicare as part of a composite rate,3 then any financial relationship between the physicians and the hospital, and their connection to the ASC/OBL, may be subject to Stark, the application of which regulations (and any appropriate exceptions) would be determined by the structure of the financial relationship between the parties (e.g., direct/indirect, compensation/ownership investment).

AKS

The AKS makes it a felony for any person to “knowingly and willfully” solicit or receive, or to offer or pay, any “remuneration,” directly or indirectly, in exchange for the referral of a patient for a healthcare service paid for by a federal healthcare program.4 Of note, interpretation and application of the AKS under case law has created precedent for a regulatory hurdle known as the one purpose test, under which test healthcare providers violate the AKS if even one purpose of the arrangement in question is to offer remuneration deemed illegal under the AKS.5

Due to the broad nature of the AKS, legitimate business arrangements may appear to be prohibited.6 In response to these concerns, Congress created a number of statutory exceptions and delegated authority to the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services (HHS) to protect certain business arrangements by means of promulgating several safe harbors,7 which set forth regulatory criteria that, if met, shield an arrangement from regulatory liability, and are meant to protect transactional arrangements unlikely to result in fraud or abuse.8 Failure to meet all of the requirements of a safe harbor does not necessarily render an arrangement illegal.9

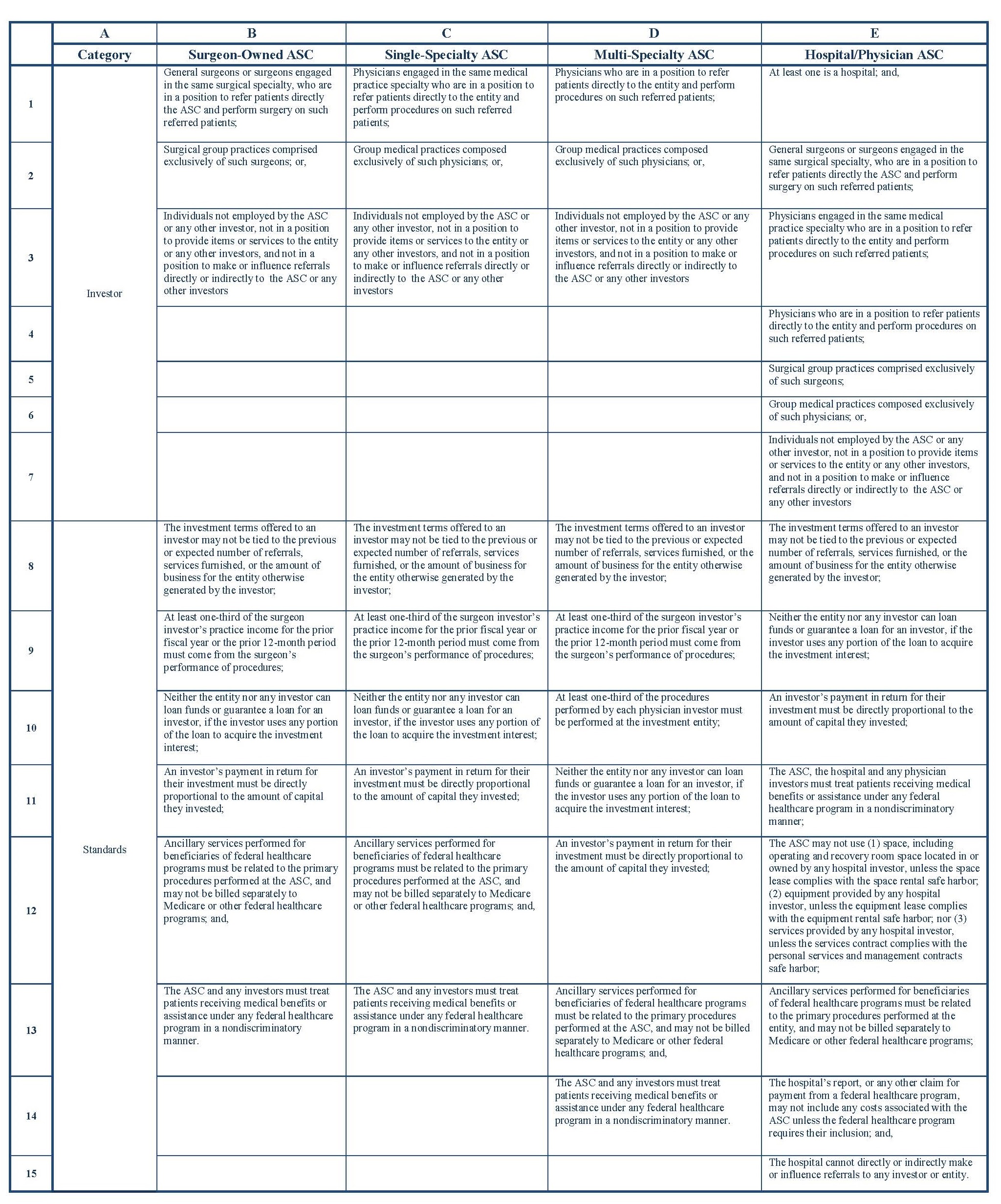

Under the AKS, ASCs and OBLs are treated differently. Specifically, ASCs must meet specific AKS safe harbor provisions, so that any ownership/investment interest in an ASC is not considered remuneration. For example, the operating and recovery room space must be exclusively dedicated to the ASC, all patients referred to the entity by an investor must be fully informed of the investor’s ownership interest, and all of the following applicable standards must be met within one of the categories set forth in the table below.

Additionally, the below safe harbors are only available to those ASCs that meet the following statutory definition:

“any distinct entity that operates exclusively for the purpose of providing surgical services to patients not requiring hospitalization and in which the expected duration of services would not exceed 24 hours following an admission. The entity must have an agreement with [the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services] CMS to participate in Medicare as an ASC…”10

Because no federal licensing is required to operate an OBL,11 they would not be considered an ASC under the AKS (as defined above). Consequently, the specific facts and circumstances related to a given transaction, such as the structure of the hospital-physician joint venture and the various financial relationships included (e.g., OBL space rental, information technology), will guide the applicability of AKS, and its associated safe harbors.

Conclusion

The continued increase in the number of healthcare services provided at ASCs and OBLs may be inhibited by the complex healthcare regulatory scheme that governs the formation, ownership, alignment, and transactions related to these outpatient entities. Consequently, these entities must take care not to enter into transactions and arrangements that may subsequently be found to be legally impermissible, so as not to become subject to substantial penalties. In fact, while the majority of hospital ASCs are operated as physician joint ventures, only about one-third in 2020 allowed their employed physicians to invest in those ASCs.12 This portion was the lowest seen in several years and is likely related to hospitals’ desire to avoid risk.13

This complex regulatory scheme presents an opportunity for valuation professionals to work with healthcare providers considering a potential transaction, as well as healthcare legal counsel, to ensure that prospective transactions and arrangements are in compliance with current laws, as well as satisfy applicable regulatory thresholds. Evidence shows that hospitals will continue to invest in ASCs,14 and they and other providers may feel more comfortable with also obtaining a certified opinion prepared in compliance with professional standards by an independent credential valuation professional (under the advice of legal counsel) and supported by adequate documentation as to whether each of the proposed elements of the transaction are both at Fair Market Value and commercially reasonable, so as to establish a risk adverse, defensible position that the transactional arrangement can withstand regulatory scrutiny.

“Limitation on Certain Physician Referrals” 42 U.S.C. § 1395nn(a).

The regulations specifically note that “DHS do not include services that are reimbursed by Medicare as part of a composite rate (for example, SNF Part A payments or ASC services identified at §416.164(a)), except to the extent that services listed in paragraphs (1)(i) through (1)(x) of this definition are themselves payable through a composite rate (for example, all services provided as home health services or inpatient and outpatient hospital services are DHS).” “Definitions” 42 C.F.R. § 411.351.

“Criminal Penalties for Acts Involving Federal Health Care Programs” 42 U.S.C. § 1320a-7b(b)(1).

“Re: OIG Advisory Opinion No. 15-10” By Gregory E. Demske, Chief Counsel to the Inspector General, Letter to [Name Redacted], July 28, 2015, https://oig.hhs.gov/fraud/docs/advisoryopinions/2015/AdvOpn15-10.pdf (Accessed 2/4/21), p. 4-5; “U.S. v. Greber” 760 F.2d 68, 69 (3d Cir. 1985).

Demske, July 28, 2015, p. 5.

“Medicare and State Health Care Programs: Fraud and Abuse; Clarification of the Initial OIG Safe Harbor Provisions and Establishment of Additional Safe Harbor Provisions Under the Anti-Kickback Statute; Final Rule” Federal Register, Vol. 64, No. 223 (November 19, 1999), p. 63518-63520.

“Re: Malpractice Insurance Assistance” By Lewis Morris, Chief Counsel to the Inspector General, United States Department of Health and Human Services, Letter to [Name redacted], January 15, 2003, http://oig.hhs.gov/fraud/docs/alertsandbulletins/MalpracticeProgram.pdf (Accessed 2/4/21), p. 1.

“Definitions” 42 U.S.C. § 416.2.

See “Survey Eligibility Criteria for Office-Based Surgery” The Joint Commission, https://www.jointcommission.org/-/media/tjc/documents/accred-and-cert/ahc/obs-eligibility-flyer.pdf (Accessed 2/4/21).

“Hospitals see opportunity, risk in ambulatory surgery centers” By Alex Kacik, January 25, 2021, Modern Healthcare, https://www.modernhealthcare.com/providers/hospitals-see-opportunity-risk-ambulatory-surgery-centers (Accessed 2/19/21).

“Exceptions: Ambulatory Surgery Centers” 42 C.F.R. § 1001.952(r) (2020).